“You can’t simply parcel this off as an Indigenous cultural rights issue. You can’t parcel it off as an economic issue. You must remain focused on the fact that old growth forests in British Columbia are at the point of extinction. We all have a responsibility to do whatever we can to protect them.”

— Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, President of the Union of BC Indian Chiefs.

Initially Indigenous people had no desire to place the sources of their survival ("natural resources") into the stream of commerce, because their value system was based on relationships and not currency. Indigenous knowledge is based on the millennia-long study of complex relationships that exist among all systems within creation.

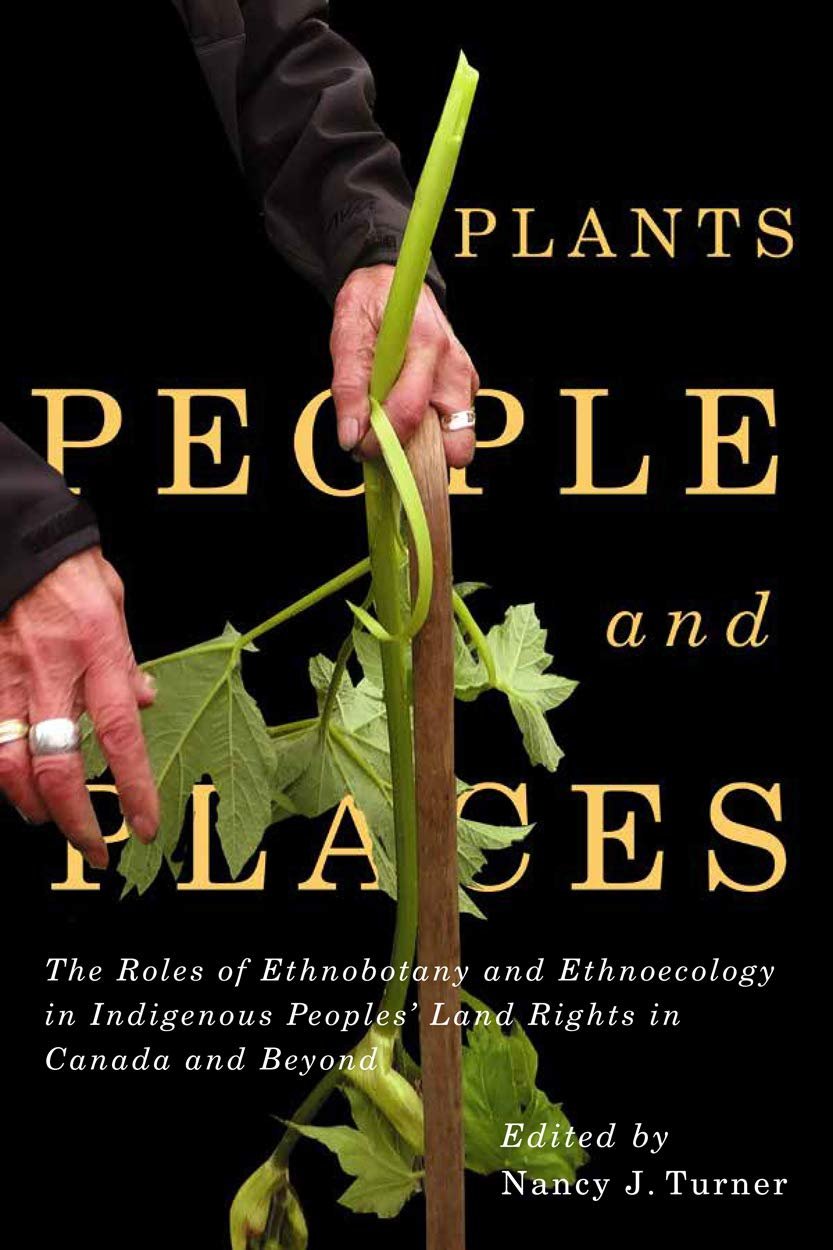

It encompasses a broad array of scientific disciplines: ethnobotany, climatology, ecology, biology, archaeology, psychology, sociology, ethnomathematics and religion. The keepers of Indigenous knowledge carry thousands of years of data on things such as medicinal plant properties, biodiversity, migration patterns, climate changes, astronomical events, and quantum physics.

It recognizes the familial relationship and acknowledges that all life is both sovereign and interdependent, and that each element within creation (including humans) has the right and the responsibility to respectfully coexist as coequals within the larger system of life. They carry the stories of countless epochs of human history, going all the way back to the beginning of human life on Mother Earth.

Western scientific ecology is embedded in the concept of scientific discovery, describing the world from the perspective of post-enlightenment Europe. An objective view used to justify social and environmental control through agriculture and bringing “civilization” by dispossessing Indigenous peoples of their land and ways of life.

The disruption of the longstanding care of species and their habitats not only has brought environmental damage but contributes to the displacement and economic "underdevelopment" of Indigenous communities. Critical Indigenous knowledge has remained outside the carefully ordered categorization of Western thought, making its holistic concepts difficult to comprehend for those who have been trained to see the world in fractured pieces. It is this fractured view that has been central to the fracturing of our societies and environment.

In Canada and elsewhere, we are witnessing the results of centuries of emphasis on profits, driven by Western ideologies that allowed the destructive exploitation of other species, Europeans domination of other peoples, and an assumption of mechanized human control over our environments. As a result, there has been an unprecedented erosion of biocultural diversity, with loss of languages and cultural knowledge paralleled by loss of species, habitat destruction and fragmentation, pollution, climate change, and economic and continuing social inequality.

The newcomers justified themselves through their assumptions of God-given rights. As Atleo explains through his description of the Nuu-chah-nulth nawtch-nawtch-cha (vision quest), "Through these visions people knew that the Creator made all things to have sacred life. Therefore all life forms were treated with respect. Then everything changed. Newcomers came with new teachings, the chief of which might be expressed as 'maximum exploitation of resources for maximum profit.' Profit took precedence over people, communities and environmental integrity. This single-minded teaching about profit has created an environmental crisis"

The stifling of creative thinking and suppression of critical analysis that results from such narrow representation erodes the overall intelligence of the entire society. And since cultural ways of being are passed on from one generation to the next, there has been very little variation in the destructive patterns that brought us to this place of collective crises. Filling the gap between our physical and subjective experiences, enabling us to understand how our internal consciousness impacts the ways that we view and experience the world around us.

The challenge for science has always been to see beyond the confines of its inherent bias and to overcome hierarchical, reductionist, and compartmentalized thinking to see the holistic patterns that are present throughout creation. The arrow of time proposed by physicists works in lab experiments and is a real observable phenomenon in closed systems. It is a true law. It’s just the wrong law to apply to beings living in open, interconnected systems.

Diversity fosters social coherence, creating more stable and harmonious relational networks, which in turn lead to more stable and harmonious societies. The more diverse a group or community, the greater the perspectives and innovations that arise and the greater the success rate for all. Human diversity is just as critical to society as biodiversity is to an ecosystem; without it there can be no healthy functioning.

After a 40 year journey to fight for Haida Values challenging the Province in government-to-government negotiations, and with forestry companies entirely excluded, a new set of possibilities became attainable - ecologically, socially, and politically. With the social order changed, a capacity for action was created on issues that were once outside the realm of possibility. The result was a dramatic change in the direction of forestry and politics on Haida Gwaii.

With conditions ripe for change, the effective and well-timed collective actions of the Haida and community actors helped to shift the structures governing land use to reflect new meanings, values, priorities, and interests. A new political landscape is now emerging on Haida Gwaii.

Marked by a fundamental shift in power, roles, and responsibilities, a new governance structure is tackling the many challenges and possibilities set in motion by the Strategic Land Use Agreement. Although still in their early phases, the political and economic models unfolding on Haida Gwaii may be a preview of what could emerge in rural communities across British Columbia.

When a cherished place or culturally important community of plants or animals is destroyed, communities also find themselves unable to pass on knowledge about this heritage to younger generations.

Learning how to find key species to harvest and process them sustainably, and to use associated vocabulary generally takes place through participatory and experiential intergenerational learning. This transmission of knowledge is not possible once the species and the places where they lived are destroyed or become inaccessable.

Although understanding how defining plant practices and knowledge in support of Indigenous legal action is valuable, focusing limited First Nations' resources on proving Indigenous rights diverts energy and attention away from essential cultural resurgence activities and frames community relationships in state-centric terms.

The "politics of distraction" that ensues from this legal focus, they say, serves as another form of "shape shifting" colonialism rather than facilitating the decolonization goal it purports to achieve.

Alternatively, practical resurgence activities have the potential both to support decolonization of landscapes at the everyday, community level and to provide concrete examples of Indigenous cultural activities that, in turn, can inform new policies and legislation at the political level in government-to-government negotiations.

The need to sustain or restore exisiting resources and habitats rather than only describing historical landscapes - is paramount.

You might not have heard of it before, but the humble Cheakamus Forest is charting new territory for sustainable timber harvest that outlaws clearcuts, respects Indigenous governance and combats the climate emergency.

At the ecosystem level of restoration, there is a growing movement toward Indigenous peoples' co-management, co-creation, and independent creation of protected and conserved areas. All of these undertakings contribute to biodiversity conservation efforts while still serving local needs, thus providing local communities with opportunities to manage access to resources as an integral element of their own responsibilities to their territories and other species.

Alongside increased opportunities for co-management and resource governance is the potential for greater recognition of, respect for, and adoption of Indigenous management principles and practices within a contemporary context.

To support this new direction, the burgeoning field of Indigenous law may provide the most influential tool for re-establishing human-plant relationships in First Nations' communities by recognizing and involving Indigenous legal traditions in land and resource management planning now and into the future.

The rather large task ahead, then, involves restoration and forging new relationships on multiple levels - ecosystem, community, law, and governance - in order to achieve true reconciliation between Indigenous and other Canadians.

Solidarity rally in Powell River features speeches about Old Growth and the effects of Colonialism. Group gathers in support of Ancient Forests.

Indigenous youth block access to Western Forest Products road in qathet region Jegajimouxw and Thich’ala lead blockade on Stillwater Mainline in solidarity with land defenders.